The Parthenon in Athens is rich in history, spanning several empires and still standing today. Visiting the Parthenon in Greece is a wonderful way to explore the country’s rich history and culture.

In This Article

- Origins and Construction

- Significance of the Parthenon’s Decoration

- What Was the Parthenon Used for?

- Other Sites to Visit on the Athenian Acropolis

- Explore Greece With Windstar Cruises

Origins and Construction

The Athenian Acropolis was sacred ground in ancient Athens. The hilltop features several important religious temples and cultural sites, the most important being the Parthenon.

Why Is the Parthenon Important?

The Parthenon was an important religious temple in ancient Athens. During the city’s peak, the building paid homage to Athena, the patron goddess of Athens and the goddess of wisdom, battle strategy and reason. She appears in many myths and often plays crucial roles, including the stories of the Trojan War.

The temple is said to have been a place for individuals to bring offerings and try to gain the goddess’s favor.

How Old Is the Parthenon?

Construction on the Parthenon began in 447 BCE and continued through 432, making it over 2,400 years old. Despite its age and rich history, the structure still stands strong. Many attribute its lasting presence to its design. Workers and designers cut the marble so precisely that they didn’t need mortar to hold it together, making it strong enough to last centuries.

Why Was the Parthenon Built?

The Parthenon was built following the Persian Wars, where the Greek city-states warded off Persian forces trying to conquer them. Historians and archeologists have evidence that another Parthenon was in construction under the original site, but it was destroyed when the Persians attacked Athens. After the wars, Athenians started building the current structure as a cultural and religious site.

Who Built the Parthenon?

While many Athenians worked to construct this iconic structure, the Parthenon is the result of several figures in Athenian history. Pericles, a crucial Athenian political leader, oversaw and commissioned the temple. He understood the importance of Athenian culture and morale after the war and likely saw how the temple could serve as a symbol for both. Many historians credit Phidias as the leading sculptor on the project, identifying his handiwork in many of the surviving designs.

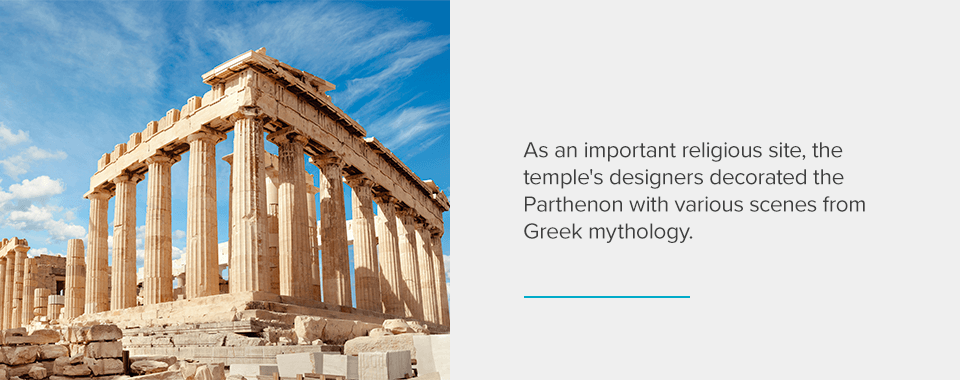

Significance of the Parthenon’s Decoration

As an important religious site, the temple’s designers decorated the Parthenon with various scenes from Greek mythology. Many of these scenes are symbolic, representing Athenian triumph over Persia. Others highlight the city’s connection to their patron goddess, Athena, who was a significant part of Ancient Greece’s polytheistic theology.

The East Pediment

Standard Greek temples like the Parthenon have many spaces where sculptors and designers placed statues, friezes and reliefs. The pediments are the large triangular spaces above the columns and entablature. Their size makes them ideal for displaying larger and more complex scenes and figures.

The east pediment of the Parthenon depicts the birth of Athena. As an important religious figure in the city, these images remind visitors that this space honors her. The image portrays Athena erupting fully formed and dressed for battle from her father Zeus’s head. Her emergence as a grown woman emphasizes her wisdom and strength, two essential godly attributes. Her armor highlights her presence on the battlefield and excellent military strategy.

The West Pediment

On the side opposite of Athena’s birth scene is another set of sculptures on the west pediment. These images show another essential moment in Athena’s life and for the city — how she became the godly patron of Athens. The pediment depicts Athena and Poseidon, god of the sea, competing for the city’s favor.

Poseidon offers them a spring, while Athena invents the olive tree and gifts it to the citizens. The people choose Athena, forever currying her favor and securing her spot as the city’s patron goddess. Because the temple was dedicated to Athena in her city state’s Acropolis, putting imagery from this story over the building had deep significance to the people religiously and culturally.

The East Metope

Metopes are parts of the entablature on Greek temples. Situated above the columns and below the pediments, entablatures are the long rectangular portions where sculptors can display more images and symbols.

They usually contain a pattern of alternating triglyphs and metopes. Triglyphs are a set of three jutting lines, almost depicting smaller columns, whereas metopes are the square spaces in between them. The Parthenon’s surviving metopes show images of mythological battles mixed with real-life figures or groups, representing the Greek victory over the Persians.

The east metope features the Gigantomachy, a mythological battle between the giants and the gods. In mythology, the giants attack Olympus, trying to claim the home of the gods for themselves. The gods pair with mortal heroes to vanquish the giants, securing their right over Greece.

The South Metope

On the south side of the temple, the metopes on this entablature highlight a different mythological battle — the Centauromachy. This battle is between centaurs, half-horse and half-human creatures, and the Lapiths, a mythical group of people from Thessaly in Greece. In the story, the Lapiths invite the centaurs to a wedding, where the creatures become very drunk and rowdy, causing a fight to break out.

The West Metope

The west metope is the last remaining metope available on the Parthenon. Like the other two, the west side is another battle scene, this time showing the Amazonomachy. In the west metope, the Athenians battle the Amazons, a tribe of highly-skilled female warriors. This battle was the first time in which the Athenians fought against foreign invaders, coming out as the victors in the end.

The Athena Parthenos

Located inside the temple, this giant statue depicted Athena in ivory and gold, towering over visitors and priests. In one hand, she held her shield, Aegis, and the goddess of victory, Nike, in the other. Unfortunately, the statue has been missing for hundreds of years, but historians understand what she might have looked like from Roman reproductions and descriptions.

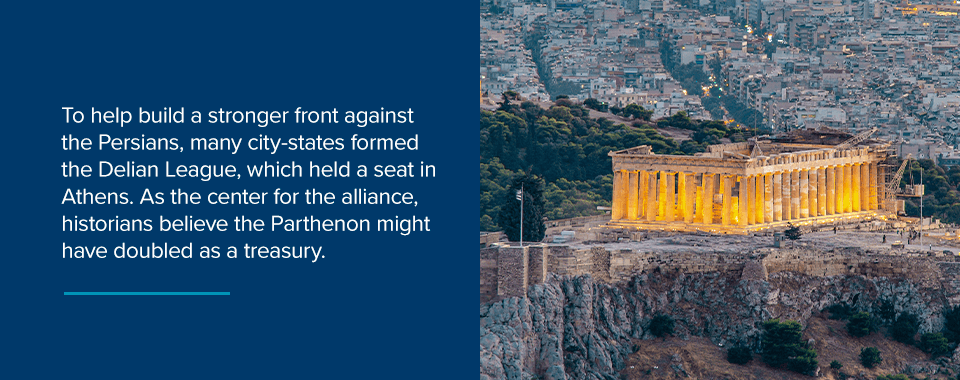

What Was the Parthenon Used for?

While many historians believe the building to be a temple to Athena, other historians believe there’s evidence that it served as a treasury. In Ancient Greece, each city was an independent state with its own government and citizens, rather than the unified country we know today.

To help build a stronger front against the Persians, many city-states formed the Delian League, which held a seat in Athens. As the center for the alliance, historians believe the Parthenon might have doubled as a treasury.

The Parthenon Throughout History

While the ancient Athenians built the Parthenon, various people occupied it over the years. What happened to the Parthenon after the fall of Ancient Greece? Here’s an overview:

Byzantine Rule

Following the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire ruled out of Constantinople, or modern-day Istanbul in Turkey. They conquered Athens in the sixth century BCE and brought Christianity with them.

After settling in the city, they outlawed all pagan worship, including Greek mythology. The Byzantines transformed the temple into a church, changing the structure but leaving many of the important sculptures. By this time in history, the Athena Parthenos was already lost.

Ottoman Rule

In 1458 CE, the Ottoman Empire expanded into Greece from the East, taking over Athens and the Acropolis. Like the Byzantines, the Ottomans transformed the space to fit their culture’s religion, enabling the temple to become a mosque.

When was the Parthenon destroyed? In 1687, the Ottomans repurposed the Parthenon again to accommodate their war with the Christian Holy League. They filled the temple with explosives, but crossfire and fighting caused the storage to catch and explode. This event caused severe damage to the Parthenon, but given that it’s still standing today, it’s also a testament to its strength and design.

Lord Elgin and the Elgin Marbles

Thomas Bruce, also known as Lord Elgin, became the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in 1799 and received permission from the sultan to excavate and salvage what was left of the Parthenon. Elgin traveled to Athens himself and picked out large portions of the remaining ruins to ship back to England on several ships.

Many of the reliefs, pediments and interior statues arrived in England between 1802 and 1812, where the British government bought them and placed them in the British Museum. Many of them remain there to this day, despite the controversy around the subject and requests submitted by Greece for their return. These marbles are named the Elgin Marbles.

Greek Reclamation

The Greeks started reclaimed their Acropolis during the War for Greek Independence, where the Greeks fought against Turkish rule and influence in the 1820s. As a central and fortified natural location, the Greeks used the Acropolis and the Parthenon as barracks for their soldiers.

Modern Day

After Greece regained its independence, restorations began in the 1970s, and the site is now a popular tourist destination. Individuals can walk amongst the ruins and imagine what it might have been like to be an Athenian coming to the temple in ancient Athens.

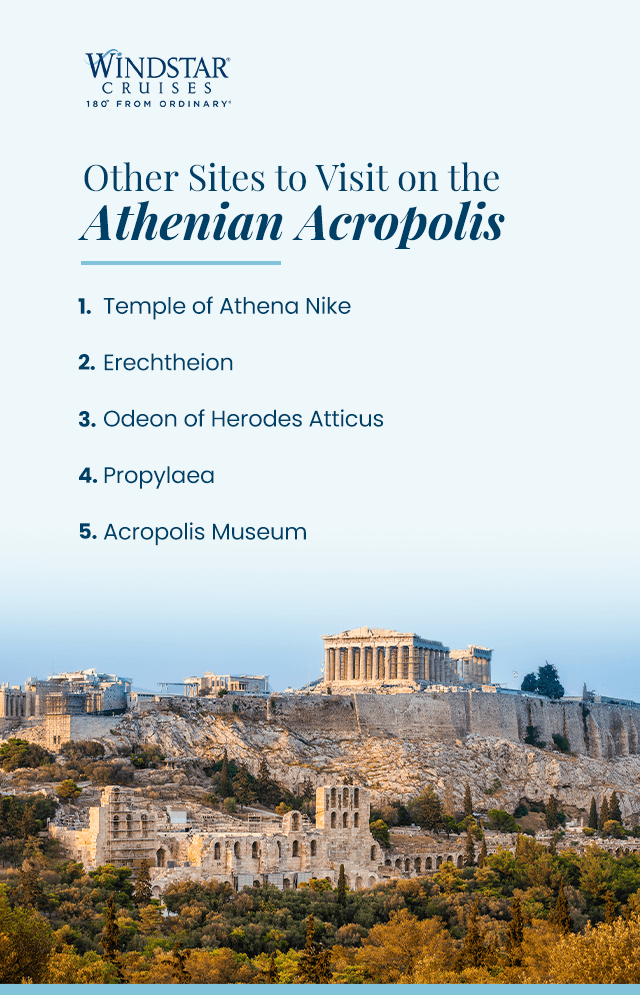

Other Sites to Visit on the Athenian Acropolis

While the Parthenon is the top attraction for many travelers in Athens, the Athenian Acropolis is home to many essential cultural and religious sites for the ancient Athenians. When visiting the Parthenon, you can take time to explore these other sites for a more comprehensive history and understanding of ancient Athens:

1. Temple of Athena Nike

Athena has multiple temples on the Acropolis, including the Temple of Athena Nike. Because the Greek gods represented multiple values and attributes, the Greeks created temples for their specific personas for more specified requests and worship. Athena Nike is a combination of the goddesses of war and victory, together symbolizing victory in battle.

Because of its meaning and dedication to Athena Nike, Athenians likely used this space to pray and show gratitude for Athenian battle victories. Friezes throughout this temple cater to its theme and purpose. They include several depictions of Athenians winning fights against other groups and city-states, like the Persians and Corinthians.

2. Erechtheion

Many historians believe this temple is one of the oldest on the Acropolis and might have undergone several dedications to different deities. One common belief is the Erechtheion was a temple to Athena Polias, another side of the city’s goddess who served as its protector.

One factor that makes this temple unique and a must-see when visiting the Acropolis is the Porch of the Maidens. Also called the Caryatid Porch, this porch lacks the traditional Ionic and Doric columns the other temples have. Instead, it showcases six identical women holding up the temple walls and looking out over the city.

3. Odeon of Herodes Atticus

Although technically constructed by the Romans, this open-air theater transports visitors through time and back to the Age of Antiquity. The theater is made from stone and overlooks modern Athens for a stunning view of the city. It hosts several performances yearly, including adaptations of Greek plays Athenians might have watched.

4. Propylaea

The Propylaea is the ancient ceremonial entrance to the Acropolis. Citizens and visitors once traveled through this temple-like structure to access the rest of the hill. It helped lead Ancient Greeks to the Parthenon for various worship and cultural needs.

5. Acropolis Museum

When you want to learn more about the art, history, architecture and archaeology surrounding the Parthenon and other structures on the Acropolis, you must visit the Acropolis Museum. The museum celebrates and highlights all archeological finds on the Acropolis, from Ancient Athens through the Roman and Byzantine eras. Technically located just below the Acropolis, it has multiple floors, and visitors are meant to view the findings chronologically.

The top floor is the most spectacular, creating a unique museum experience for visitors. On a skewed orientation, designers intended to match the direction of the original Parthenon. The floor also has glass walls to allow natural light to filter in and enable visitors to view the art in the same way as the ancient Athenians.

After admiring the original marble statues on the top floor, the museum encourages visitors to work toward the ground level to experience the other art and archeological finds on display. While the top floor is just for the Parthenon, the other floors celebrate all the buildings on the Acropolis, from the Propylaea to the Erechtheion. The museum gives travelers a comprehensive overview of its history and close-up looks at the art and findings.

Explore Greece With Windstar Cruises

From picturesque islands on crystal blue waters to larger-than-life archeological sites, travelers in Greece can create the perfect getaway with a diverse itinerary. At Windstar Cruises, we offer cruises through the islands and mainland ports for a Mediterranean experience unlike any other.

With smaller ships, Windstar Cruises can create more unique cruises for passengers because we can fit into smaller ports. During your stay, our staff can get to know you better for a more personalized journey that meets your needs. Planned excursions and culinary experiences enable travelers to experience some of the best sites your destinations can offer.

Discover our available cruises through Greece today and learn why you should travel with Windstar Cruises.

Not sure about the part in this article where it says that the byzantines conquered Athens and all that because I’m pretty sure that’s not how it worked. I think that part needs to be edited but I’m not a historian so I’d be the wrong one to actually do that.

Hi, Curt, thanks for your note! We got the info here, and I double-checked and though I’m no expert, the Byzantines did appear to conquer Athens. Checked it here: https://www.britannica.com/place/Greece/Byzantine-recovery. Thanks — Carolyn